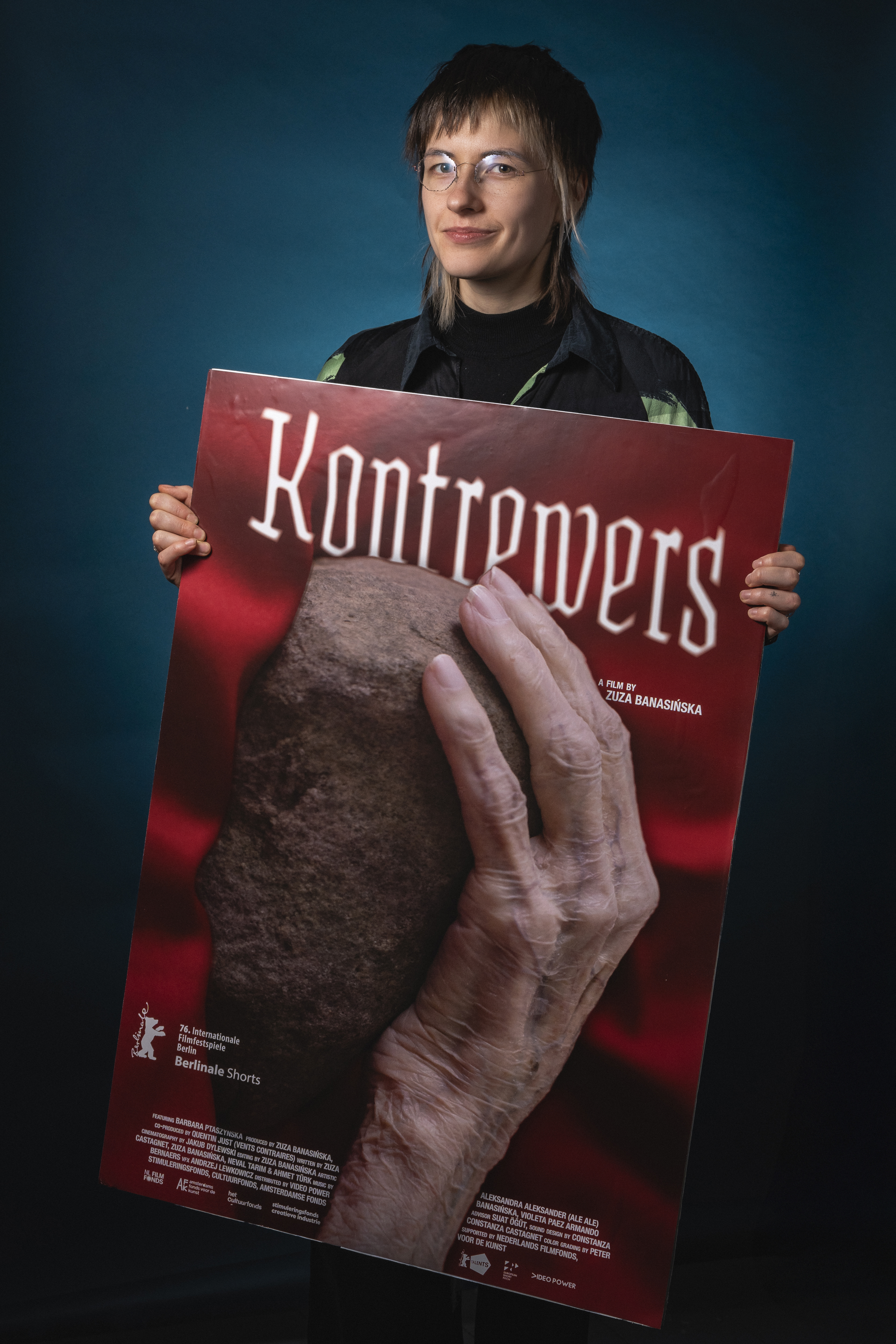

The artist and filmmaker Zuza Banasińska was born in Warsaw, Poland and is currently based in Amsterdam. They studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków, the University of the Arts in Berlin and the Sandberg Instituut in Amsterdam. Their work has screened internationally at film festivals including Rotterdam, New York and Visions du Réel. Grandmamauntsistercat was selected for over 100 festivals including the Berlinale Forum Expanded in 2024 and won the Teddy Award for Best Short Film.

What was your starting point for „Kontrewers“?

When I first encountered the Kontrewers stone, I became absolutely fascinated by it. It’s a large stone found in central Poland, whose surface bears petroglyphs that have accumulated wildly divergent interpretations over time. These range from speculative archaeological readings, proof of alien existence, traces of shamanic rituals, and representations of gods never before found in Europe, to a local folktale about violence and possession.

At first, I tried to squeeze all of this into a short film, but failed multiple times. I am now developing a feature from this material, and for the short I decided to focus on a single interpretation: the folktale of a possessed girl who used the stone as a murder weapon, and whose exorcism was believed to cause the petroglyphs to appear.

What fascinated me was the supernatural genealogy of an image tied to a story of gendered violence, and the quiet endurance of that violence in the materiality of the stone itself. Before its medicalization and moralization under Christianity, possession functioned as a way of naming communication with that which was non-verbal, temporally distant, or ontologically unstable. Later, it became a label disproportionately applied to women and other marginalized subjects: bodies imagined as permeable, excessive, and in need of control. In Kontrewers, I reclaim possession as a methodology: a relational state in which boundaries are negotiated rather than enforced.

While researching the stone, I realized that I was also searching for a personal entry point into this structure. I had always envisioned an older woman playing a role in the film, drawn to how aging renders the body increasingly unreadable within normative systems of value. This search eventually led me to my grandmother. Fascinated by the resistance of her hands and the vulnerability of her skin, I invited her into the film. Working with her transformed it from an investigation of a legend into an intimate encounter with mortality, repression, and aliveness.

Possession became a methodology of filming: I began to see my role as a filmmaker as both possessing her story and allowing myself to be possessed in return. It became a constant negotiation of boundaries, including those between fiction and documentary. We had only four days of filming, and only a couple of hours per day, as she would get tired quickly. My favorite moments emerged outside the camera, in our conversations about life, death, faith, and the folktale itself. During these recorded interviews, I could succumb to her passage of time: to slowness, long silences, forgetting and returning. The process was quite extraordinary; I have never felt closer to her than in those moments, and later while relistening to her voice, her breath, even her burps.

The ghost in the film mediates our encounter, introducing a necessary distance that paradoxically enables closeness. Through it, communication becomes oblique rather than direct, allowing both my grandmother and myself to approach memories, and inherited traumas without fixing them into confession or explanation.

Do you have a favorite moment in the film? Which one and why this one in particular?

I have two favorite moments that I always knew will have their place in the film, before any of the other elements came in. Both of them reflect that which cannot be expressed in words, but is carried through gestures, textures and voice.

One is the first scene, with the crying eel and the exorcism paintings. The eel was part of the film even before my grandmother. We filmed it near Kontrewers in an oceanarium and the eel looked like pure intensity, pure life. It became a vessel for the pain and loss that cannot be verbalized or metabolized and that keeps on resurfacing through generations. Just as my grandmother sits on the passage between life and death, I see the eel on the borderline of life and non-life. The ghost belongs to both.

Approaching possession from another angle, I wanted to begin with exorcism, which I see not as a cure, but as an underlying cause of possession. Rather than a release, as it is often framed through Christianity, exorcism becomes a resurfacing of violence that lingers and is absorbed by history and matter through repression. The eel symbolizes this resurfacing, so I paired it with something more visceral, direct, and “documentary”: the repetitive iconography of Christian exorcism paintings, accompanied by the sound of an exorcism recording taken from a YouTube preacher.

The second scene is the soft Ave Maria singing prayer as a ritual of possession. Not only was it a pleasure to edit, especially with Constanza Castagnet’s reworking of her singing, it was also emotionally very potent for me.

As a teenager, my grandmother dreamed of becoming a singer and studying opera, but the war interrupted those plans. I always sensed a performer in her, which is why this sequence feels so important. Through singing and gesture, she expresses something she would never allow herself to articulate verbally.

Her voice and movements carry sensuality, depth, and pain as material traces, much like the marks on the stone. The prayer becomes the space where she, the ghost and me connect, communicating through sound and movement rather than language. For me, this is the culmination of possession: a moment where she is no longer entirely herself, allowing herself to be guided by an “other” within. It is not confession in a Christian sense, but a transfiguration of the repressed into gesture, voice, and material relation.

What do you like about the short form?

My process does not follow a typical filmmaking structure. It often begins with images, sounds, and fragments of information that only gradually become a story through cycles of editing, filming, recording, and re-editing. I think of myself first and foremost as an editor, and the short form allows me to experiment freely with rhythm, density, and resonance, continuously reshaping the film on the timeline. It also mirrors how memory operates in my work: non-linear, fragmentary, and unresolved. In this sense, the short form becomes a precise container for my methodology, where I can attend closely to every sound, detail, and cut. It allows me to treat excess as a method: connecting seemingly separate narratives and modes of narration to see what emerges through their juxtaposition.

*************************************************************************************

PRESS REVIEWS